Introduction

OSVR is an open source software platform and VR goggle. Sensics and Razer launched OSVR 18 months ago with the intent of democratizing VR. We wanted to provide an open alternative to walled-garden, single-device approaches.

It turns out that others share this vision. We saw exponential growth in participation in OSVR. Acer, NVIDIA, Valve, Ubisoft, Leap Motion and many others joined the ecosystem. The OSVR goggle – called the Hacker Development Kit – has seen several major hardware improvements. The founding team and many other contributors expanded the functionality of the OSVR software.

I’d like to describe how I hope to see OSVR develop given past and present industry trends.

Increased Device Diversity leads to more Choices for Customers

Trends

An avalanche of new virtual reality devices arrived. We see goggles, motion trackers, haptics, eye trackers, motion chairs and body suits. There is no slowdown in sight: many new devices will launch in the coming months. What is common to all these devices? They need software: game engine plugins, compatible content and software utilities. For device manufacturers, this software is not a core competency but ‘a necessary evil’. Without software, these new devices are almost useless.

At the same time, content providers realize it’s best not to limit the their content to one device. The VR market is too small for that. The more devices you support, the largest your addressable market becomes.

With such rapid innovation, what was the best VR system six months ago is anything but that today. The dream VR system might be a goggle from one vendor, input devices from another and tracking from a third. Wait another six months and you’ll want something else. Does everything need to come from the same vendor? Maybe not. The lessons of home electronics apply to VR: you don’t need a single vendor to make all your devices.

This ‘mix and match’ ability is even more critical for enterprise customers. VR arcades, for instance, might use custom hardware or professional tracking systems. They want a software environment that is flexible and extensible. They want an environment that supports ‘off-the-shelf’ products yet extends for ‘custom’ designs.

OSVR ImplicationsOSVR already supports hundreds devices. The up-to-date list is here:

http://osvr.github.io/compatibility/ . Every month, device vendors, VR enthusiasts and the core OSVR team add new devices. Most OSVR plugins (extension modules) are open-sourced. Thus, it is often possible to use an existing plugin as baseline for a new one. With every new device, we come closer towards achieving universal device support.

A key OSVR goal is to create abstract device interfaces. This allows applications to work without regards to the particular device or technology choice. For example, head tracking can come from optical trackers or inertial ones. The option of a a “mix and match” approach overcomes the risk of a single vendor lock-in. You don’t change your word processor when you buy a new printer. Likewise, you shouldn’t have to change your applications when you get a new VR device.

We try to make it easy to add OSVR support to any device. We worked with several goggle manufactures to create plugins for their products. Others did this work themselves. Once such a plugin is ready, customers instantly gains access to all OSVR content. Many game engines – such as Unity, Unreal and SteamVR- immediately support it.

The same is also true for input and output peripherals such as eye trackers and haptic devices. If developers use an API from one peripheral vendor, they need to learn a new API for each new device. If developers use the OSVR API, they don’t need to bother with vendor-specific interfaces.

I would love to see more enhancements to the abstract OSVR interfaces. They should reflect new capabilities, support new devices and integrate smart plugins.

More People Exposed to more VR Applications in More Places

Trends

Just a few years ago, the biggest VR-centric conference of the year had 500 attendees. Most attendees had advanced computer science degrees. My company was one of about 10 presenting vendors. Today, you can experience a VR demo at a Best Buy. You can use a VR device on a roller coaster. With a $10 investment, you can turn your phone into a simple VR device.

In the past, to set up a VR system you had to be a geek with plenty of time. Now, ordinary people expect to do it with ease.

More than ever, businesses are experimenting with adopting VR. Applications that have always been the subject of dreams of are becoming practical. We see entertainment, therapy, home improvement, tourism, meditation, design and many other applications.

These businesses are discovering that different applications have different hardware and software requirements. A treadmill at home is not going to survive the intensive use at a gym. Likewise, a VR device designed for home use is not suitable for use in a high-traffic shopping mall. The computing and packaging requirements for these applications are different from use to use. Some accept a high-end gaming PC, while others prefer inexpensive Android machines. I expect to see the full gamut of hardware platforms and a wide variety of cost and packaging options.

OSVR Implications

“Any customer can have a car painted any color that he wants so long as it is black”, said Henry Ford. I’d like to see a different approach, one that encourages variety and customization.

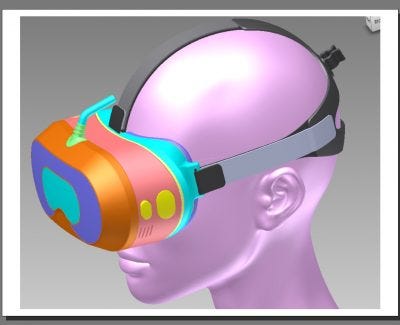

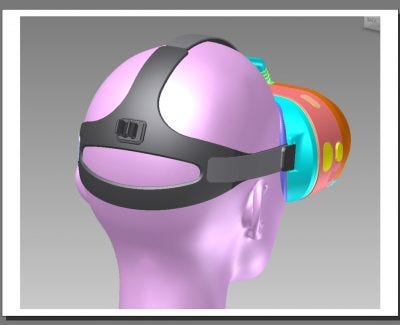

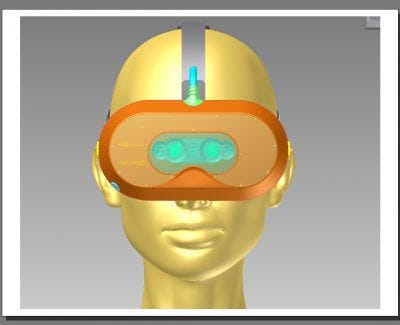

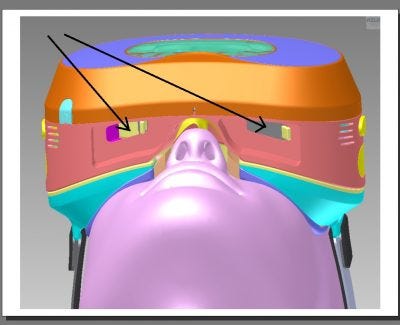

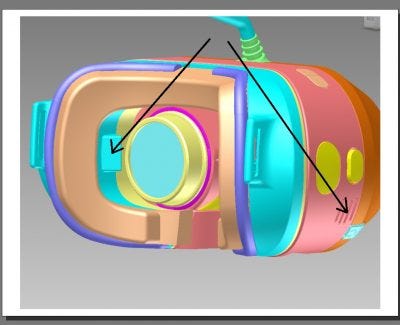

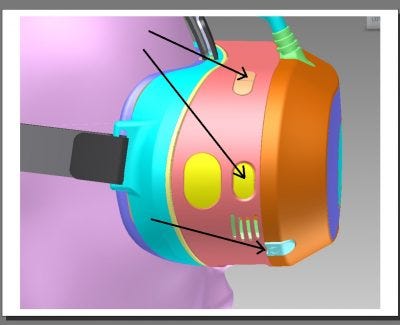

On the hardware side, Sensics is designing many products that use OSVR components. For instance, our “Goggles for public VR” use OSVR parts in an amusement park goggle. We also help other companies use OSVR components inside their own packages. For those that want to design their own hardware, the OSVR goggle is a good reference design.

On the software side, I would like to see OSVR expand to support more platforms. I’d like to see better Mac support and more complete coverage of Android and Linux platforms. I’d like to see VR work well on mid-range PCs and not limited to the newest graphics cards. This will lower the barriers to experience good VR and bring more people into the fold. I’d like to see device-specific optimizations to make the most of available capabilities. The OpenCV image processing library has optimizations for many processors. OSVR could follow a similar path.

Additionally, it is important to automate or at least simplify the end-user experience. Make it as close to plug-and-play as possible . The task of identifying available devices and configuring them should be quick and simple.

Simplicity is not limited to configuration. We’d like to see easier ways to choose, buy and deploy software.

Reducing Latency is Becoming Complex

Trends

Presence in VR requires low latency, and reducing latency is not easy. Low latency is also not the result of one single technique. Instead, many methods work together to achieve the desired result. Asynchronous time warp modifies the image just before sending it to the display. Predictive tracking lowers perceived latency by estimating future orientation. Direct mode bypasses the operating system. Foveated rendering reduces render complexity by understanding eye position. Render masking removes pixels from hidden areas in the image.

If this sounds complex, it is just the beginning. One needs to measure optical distortion and correct it in real-time. Frame rates continue to increase, thus lowering the available time to render a frame. Engines can optimize rendering by using similarities between the left- and right-eye images. Techniques that used to be exotic are now becoming mainstream.

A handful of companies have the money and people to master all these techniques. Most other organizations prefer to focus on their core competencies. What should they do?

OSVR implications

A key goal of OSVR is to “make hard things easy without making easy things hard”. The OSVR Render Manager examplifies this. OSVR makes these latency-reduction methods available to everyone. We work with graphics vendors to achieve direct mode through their API. We work with game engines to provide native integration of OSVR into their code.

I expect the OSVR community to continue to keep track of the state of the art, and improve the code-base. Developers using OSVR can focus away from the plumbing of rendering. OSVR will continue to allow developers to focus on great experiences.

The Peripherals are Coming

Trends

A PC is useful with a mouse and keyboard. Likewise, A goggle is useful with a head tracker. A PC is better when adding a printer, a high-quality microphone and a scanner. A goggle is better with an eye tracker, a hand controller and a haptic device. VR peripherals increase immersion and bring more senses into play.

In a PC environment, there are many ways to achieve the same task. You select an option using the mouse, the keyboard, by touching the screen, or even with your voice. In VR, you can do this with a hand gesture, with a head nod or by pressing a button. Applications want to focus on what you want to do rather than how you express your wishes.

More peripherals mean more configurations. If you are in a car racing experience, you’d love to use a rumble chair if you have it. Even though Rumble chairs are not commonplace, there are several types of them. Applications need to be able to sense what peripherals are available and make use of them.

Even a fundamental capability like tracking will have many variants. Maybe you have a wireless goggle that allows you to roam around. Maybe you sit in front of a desk with limited space. Maybe you have room to reach forward with your hands. Maybe you are on a train and can’t do so. Applications can’t assume just one configuration.

OSVR implications

OSVR embeds Virtual Reality Peripheral Network (VRPN), an established open-source library. Supporting many devices and focusing on the what, not the how is in our DNA.

I expect OSVR to continue to improve its support for new devices. We might need to enhance the generic eye tracker interface as eye trackers become more common. We will need to look for common characteristics of haptics devices. We might even be able to standardize how vendors specify optical distortion.

This is a community effort, not handed down from some elder council in an imperial palace. I would love to see working groups formed to address areas of common interest.

Turning Data into Information

Trends

A stream of XYZ hand coordinates is useful. Knowing that this stream represents a ‘figure 8’ is more useful. Smart software can turn data into higher-level information. Augmented reality tools detect objects in video feeds. Eye tracking software converts eye images into gaze direction. Hand tracking software converts hand position into gestures.

Analyzing real-time data gets us closer to understanding emotion and intent. In turn, applications that make use if this information can become more compelling. A game can use gaze direction to improve the quality of interaction with a virtual character. Monitoring body vitals can help achieve the desire level of relaxation or excitement.

As users experience this enhanced interaction, they will demand more of it.

OSVR Implications

Desktop applications don’t have code to detect a mouse double-click. They rely on the operating system to convert mouse data into the double-click event. OSVR needs to provide applications with both low-level data and high-level information.

In “OSVR speak”, an analysis plugin is the software that converts data into information. While early OSVR work focused on lower-level tasks, several analysis plugins are already available. For example, DAQRI integrated a plugin that detects objects in a video stream.

I expect many more plugins will become available. The open OSVR architecture opens plugin development to everyone. If you are an eye tracking expert, you can add an eye tracking plugin. If you have code that detects gestures, it is easy to connect it to OSVR. One might also expect a plugin marketplace, like an asset store, to help find and deploy plugins.

Augmenting Reality

Market trends

Most existing consumer-level devices are virtual reality devices. Google Glass has not been as successful as hoped. Magic Leap is not commercial yet. Microsoft Hololens kits are shipping to developers, but are not priced for consumers yet.

With time, augmented-reality headsets will become consumer products. AR products share many of the needs of their VR cousins. They need abstract interfaces. They need to turn data into information. They need high-performance rendering and flexible sensing.

OSVR Implications

The OSVR architecture supports AR just as it supports VR. Because AR and VR have so much in common, many components are already in place.

AR devices are less likely to tether to a Windows PC. The multi-platform and multi-OS capabilities of OSVR will be an advantage. Wherever possible, I hope to continue and see a consistent cross-platform API for OSVR. This will allow developers to tailor deployment options to the customer needs.

Summary

We designed OSVR to provide universal connectivity between engines and devices. OSVR makes hard things easy so developers can focus on fantastic experiences, not plumbing. It is open so that the rate of innovation is not constrained by a single company. I expect it to be invaluable for many years to come. Please join the OSVR team and myself for this exciting journey.

To learn more about our work in OSVR, please

visit this page

This post was written by Yuval Boger, CEO of Sensics and co-founder of

OSVR. Yuval and his team designed the OSVR software platform and built key parts of the OSVR offering.